“African culture has become the continent’s soft power.”

Declan Walsh for The New York Times

The emergence of African-produced

Media in American markets

Why It matters

The narrative power the United States and the West have had over Africa has been determinantal to the continent. Stories painting Africa as backward and in need of intervention to achieve Western standards of development have led to its exploitation for generations.

The past few years have seen an emergence of movies and shows produced on the continent, particularly from Nigeria and South Africa, across U.S. media platforms, namely streaming sites like Netflix, Amazon Prime, and Disney+. This media is Africa’s soft power and can help break the West’s hold on its perception.

“Scriptwriters and animators are shaking off the clichéd image of a continent defined by famine and conflict to tell new stories — frothy reality shows, gritty gangster tales and even children’s cartoons, made in Africa by Africans” (Walsh and Morales 2023).

Why is it important to understand how and why this emergence is happening?

Intentions

Modeling

partnerships

Understanding why U.S. media companies are now taking an interest in African-produced movies and shows can shed light on their intentions for doing so.

Is this interest reactionary, or what Anandam Kavoori calls an “acting on,” to the social unrest of the early 2020s (Kavoori 2009)? Does the U.S. have a genuine interest in broadcasting African-led content?

Entering U.S. markets can reap financial benefits - “Netflix has spent $175 million in Africa since 2016” (Walsh and Morales 2023).

Other African countries that want to enter U.S. markets can model Nigeria and South Africa.

Other media markets within the U.S. and in other countries can work with African producers by following best practices.

They can break the cycle of perpetuating harmful narratives by showcasing content that reflects the dignity and diversity of the continent.

analytical approaches

Soft

power

“Occurs when one country gets other countries to want what it wants” (Nye 1990, 166).

economic

imperative

Understanding and engaging with economies of other countries is important for being competitive in the global economy (Nakayama and Halualani 2010).

subaltern flows

“A two-way flow of communication and cultural practices,” a so-called “globalization from below” (Thussu 2018, 192).

Ethical

imperative

“Concerned with the ethical principles of conduct that help govern the behaviors of individuals and groups (Krumrey 2022).

U.S. control over media markets

As a global power, the U.S. influences the attitudes, opinions, and narratives regarding countries and peoples who exercise less power on the global stage.

Why It matters

“Communication has always been critical to the establishment

and maintenance of power over distance” (Thussu 2018, 1).

The U.S. monopoly over global media markets dictates what narratives are worth sharing. This monopoly can frame how people from different cultures are viewed globally, either to their benefit or detriment.

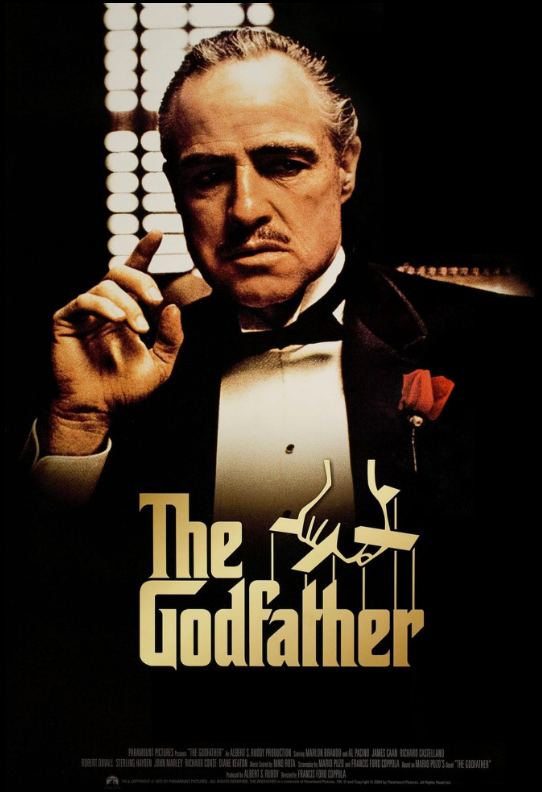

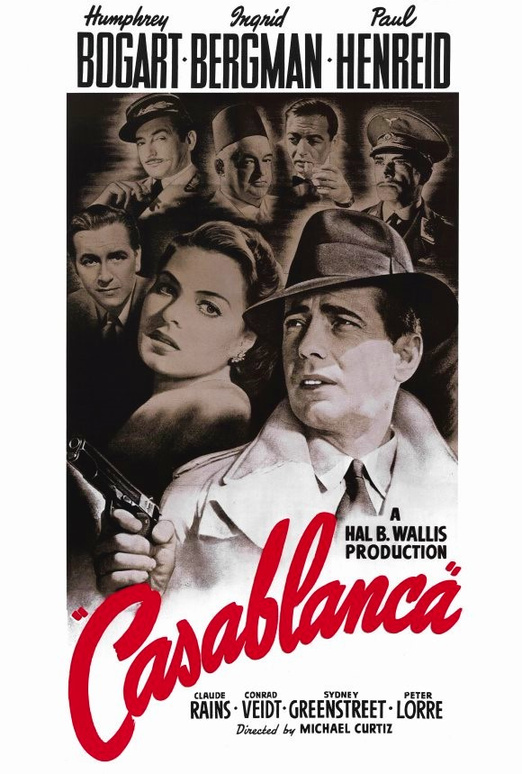

“The internationalization of a new mass culture [...] began with the film industry. [...] The development of independent studios between 1909 and 1913 led to the growth of the Hollywood film industry which was to dominate global film production. The systematic industrialization and commercialization of cinema contributed to American cultural exports (Bakker, 2008)” (Thussu, 2018, 13).

u.s. global media dominance today

Eight of the ten world’s largest media companies are based in the U.S. according to the 2023 Forbes Global 2000 rankings (Dellatto 2023).

Seven of the ten world’s most popular streaming sites are based in the U.S. according to FlixPatrol (“Top Streaming Services by Subscribers FlixPatrol” n.d.).

top media companies

top Streaming sites

- Comcast Corporation

- Walt Disney Company

- Charter Communication

- Warner Bros. Discovery

- Omnicon Group Inc.

- Fox

- DISH Network

- Paramount

- Netflix

- Amazon Prime

- Disney+

- Max (formerly HBO Max)

- Paramount+

- Hulu

- Apple TV

historical Overview of african-focused Film

Focusing on film for this analysis, the history of African-focused media sees a shift from media about Africa made by Westerners to media by Africans made by Africans.

LATE 19th & EARLY 20th CENTURY

Filmmakers in Egypt and Tunisia, among the earliest on the continent, screened films in major cities across both countries (“Alexandria Why? The Beginnings of the Cinema Industry in Alexandria, AlexCinema” n.d.) (Leaman 2003).

Examples: The Girl from Carthage, Laila

Colonial era

Africa was largely depicted by Western filmmakers who reproduced narratives that exoticized them or portrayed them as savages in the view of colonizers (Hayward 2005, 402).

Examples: King Solomon’s Mines, Voodoo Vengeance

A few anti-colonial films were produced during this era. Western filmmakers challenged colonial perceptions and began working with Africans on their projects (Thackway 2003).

Examples: Statues Also Die, The Human Pyramid

POST-INDEPENDENCE and 1970s

Ousmane Sembène, a Senegalese filmmaker known as the “father of African film,” created Black Girl (1966) which won international recognition. Filmmakers during this period used film as a political tool for rectifying the colonial image of Africa (Thackway 2003, 1-6).

The Panafrican Film and Television Festival of Ouagadougou and The Pan African Federation of Filmmakers were established to support African filmmakers.

Examples: Soleil O, Kaddu Beykat

1980s & 1990s

Malian filmmaker Souleymane Cissé's Yeelen (1987) was the first film made by a Black African to compete at the Cannes Film Festival (Neophytou 2018). Thanks to the availability of cheap video recorders, Nigerian cinema exploded on the scene, putting Nollywood on the map (Tiendrebeogo and et al. 2021, 186).

Examples: Guimba, Glamour Girls

2000s & 2010s

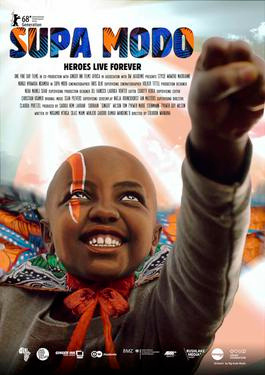

The Africa Movie Academy Awards launched in 2005, with the mission “to promote the African culture, encourage professionalism in the movie industry and offer professional development and networking opportunities” (“About Us – Africa Movie Academy Awards” n.d.). Films focus on universal problems like migration and international relations, and themes of Africanfuturism and Afrofuturism emerge in films.

Examples: Waiting for Happiness, Pumzi

2020s

Private U.S. companies have shown a commercial interest in African productions (Tiendrebeogo and et al. 2021, 40). The boom of streaming platforms has seen companies partnering with African producers to bring locally-made content to U.S. audiences. In early 2022, “Netflix pledged to invest at least $56 million (ZAR 920 million) across four productions in South Africa in 2022-2023” (Roxborough 2022).

Examples: How to Ruin Christmas, Queen Sono

According to UNESCO, the interest in acquiring and developing content was “spurred by a new focus on Black content born out of the 2020 Black Lives Matter movement and inspired by the global success of the blockbuster Black Panther” (Tiendrebeogo and et al. 2021, 40).

LOOKING AHEAD

Globally, there is a growing demand for African-produced content, unlocking new funding opportunities from other countries and from within the continent itself. In 2020, Afreximbank announced the launch of a US $500 million facility to support African creative industries and is now working on the first pan-African film funding mechanism (Tiendrebeogo and et al. 2021, 40).

“The histories of Africans as well as former colonies – written, authorized and validated by non-Africans – have been characterized by ’exclusions, erasures, silences, distortions and arbitrary fictions,’ and because of this, filmmakers and others have taken on the task of ‘purging their histories of imposed remembrances’ and privileging the voices of hitherto suppressed subjects in order to construct different histories of Africa and Africans” (Cham 2011).

Analyzing the context

Ethical

imperative

After the colonial era, African filmmakers understood the ethical imperative of returning dignity and agency to Africa’s portrayal in the global media. Howard University professor Mbye Cham states this “is part of a worldwide film movement aimed at constructing and promoting an alternative popular cinema, one that corrects the distortions and stereotypes propagated by dominant western cinemas” (Cham 2011). Telling complex stories that represent their realities was necessary to fight colonial dominance of the continent.

Only more recently has the U.S. invested in African-produced media consistently. However, their imperative is concerned with issues situated within American contexts. Investment as a response to the 2020 BLM protests is to the benefit of media companies’ image of being “diverse,” as activists called out businesses for their historic negligence of supporting marginalized peoples.

economic

imperative

With the worldwide success of Marvel’s Black Panther (2018), the 17th highest grossing film of all time with over $1 billion in ticket sales, U.S. media companies recognized a chance to cash in on media made by African talent (“Black Panther” n.d.). However, while the movie is set on the continent and displays the richness of African cultures, it was mostly created with talent not local to Africa. The vehicle for driving this imperative was seeing the success of what Western talent produced using African cultures before investing money directly into the continent itself.

Additionally, while Black Panther was praised by Black American audiences for its positive representation of Blackness - "They’re going to see themselves reflected in a huge way that they just haven’t been able to see before,” Jamie Broadnax is quoted saying in USA Today (Truitt 2018) - it was criticized by some African critics for its neocolonialist imagining of Africa. Patrick Gathara for The Washington Post states “it is a movie about a divided, tribalized continent, discovered by a white man who wants nothing more than to take its mineral resources” (Gathara 2021).

subaltern

flows

Driven by African filmmakers’ ethical imperative for producing their own stories and their desire to create high-quality works that circulate through local and global markets and festivals, African media has created a subaltern flow of communication that helps disrupt the dominant one-way flow from U.S. media companies.

Communication scholar Daya Kishan Thussu states “Such growing visibility [of subaltern flows] is an indication of the changing power structures in the world (Thussu, 2007a; Nordenstreng and Thussu, 2015)” and that “this has coincided with the relative economic decline of the West, to complement, if not challenge, US hegemony in the field of media and communication (Nordenstreng and Thussu, 2015)” (Thussu 2018, 192). With the balance of power shifting in global media flows, African producers have more power to distribute media to U.S. and Western markets.

Nigerian Media historical context

As Africa’s most populous country at 230,842,743 as of 2023 (“Nigeria” 2023) and its largest economy, Nigeria’s film industry, Nollywood, produces films that circulate the globe, “creating a ‘pan-African and global form of popular culture’ (Jedlowski, 2013: 31)” (Thussu 2018, 211).

After gaining independence in 1960, Nigerians took ownership of cinemas from foreigners, leading to more productions from native Nigerians (Tiendrebeogo and et al. 2021, 186).

The post-independence period saw box office hits including Wale Adenuga’s Papa Ajasco (1984) and Moses Olaiya’s Mosebolatan (1985), laying the foundation for Nollywood’s domestic success (Tiendrebeogo and et al. 2021, 186).

During the 1990s, cheaply made videos shot on VHS were circulated widely through the streets. With poorer production values compared to movies released in cinemas, these films “told stories that pandered to the lowest common denominator – sex, violence and the colonial leftover messages of Christian values” (Mhando 2009, 23).

When no films could be imported or made locally, these easy-to-make videos satiated an entertainment-starved populace. “Not impeded by the ‘over-sophistication’ and ‘perfect’ image, as western audiences are wont to be, African film-makers took the opportunity to turn the video format into a production format” (Mhando 2009, 24).

In the 2000s with the establishment of Silverbird Cinemas, one of the largest cinema chains in West Africa, filmmakers sought to raise their production values to distribute their films on the big screen. Filmmakers from the 1990s also took on ambitious storytelling (Tiendrebeogo and et al. 2021, 186). This led to the release of numerous record-setting films including 30 Days in Atlanta (2014), The Wedding Party (2016), Chief Daddy (2018), King of Boyz (2018), and Sugar Rush (2019) (Tiendrebeogo and et al. 2021, 186).

Films with high production values made their way to film festivals like the Sundance Film Festival (Tiendrebeogo and et al. 2021, 187).

Nigeria’s profile as a cinematic powerhouse was also bolstered by diasporan Nigerian actors, including David Oyelowo (Selma), John Boyega (Star Wars), Chiwetel Ejiofor (Doctor Strange), Sophie Okonedo (Hotel Rwanda) and others (Tiendrebeogo and et al. 2021, 187).

Recently (2020s), Hollywood studios partnered with Nigerian filmmakers to acquire or develop local content (Tiendrebeogo and et al. 2021, 188). Netflix has acquired numerous properties and developed partnerships with production studios, and Disney signed a deal with Nigerian-Ugandan company Kugali to produce an original sci-fi series titled Iwaju (Tiendrebeogo and et al. 2021, 188).

nigerian media emergence

Over the past century, Nigerians took back control of their representation from Westerners/colonialists by making their own media, representing Nigeria as Nigerians wanted to be viewed.

See sources through link above.

Nigerian-U.S. Media relationship

Nigeria as a whole, like most countries and cultures of the African diaspora, is often lumped into a portrayal of Africa as a whole, which “ignores the actualities and specificities of social and economic processes that occur in the continent (Jarosz, 1992)” (Moses, Ikeji, and Jorshe 2021). I argue that U.S. media companies lack knowledge of the histories and cultural complexities of Nigerian culture (compared to European countries), leading to the lack of U.S.-made media that portray the country as a whole. U.S. media typically represents Nigeria through individual characters or families.

Whether U.S.-based companies should produce more of their own portrayals of Nigeria is debatable, but when looking at individual Nigerian characters, the portrayals tend to be more three-dimensional. Television characters like Abishola Adebambo (Bob Hearts Abishola), Chidi Anagonye (The Good Place), and Darius Epps (Atlanta) showcase characters that break from the stereotypes of Africans as lacking agency (Okonjo n.d.).

Analyzing the context

economic

imperative

While the home video boom of the 1980s and 1990s popularized Nigerian-made media, Nigerian creators saw the economic imperative of adopting Western styles of production. Raising the production values to the levels of the West allowed Nigerian creators to distribute their media through cinemas and international film festivals, leading to more revenue than they would get through selling their creations through local vendors.

subaltern

flows

Off the heels of the colonial era, Nigerian creators began to distribute their own stories that sought to rectify their global colonial image, challenging Western media control and dominance. This subaltern flow challenges the one-way flow of media into Nigeria from the U.S., which dominates global media markets.

South African Media historical context

While South Africa is a prime location for filming U.S. productions (Homeland, The Avengers, Invictus, Blood Diamond), the country boasts its own influential film industry.

South Africa was one of the first countries to witness motion pictures when a theater opened in Johannesburg in 1895. During the colonial period, the country’s first feature film, The Great Kimberley Diamond Robbery was shot in 1910, and Isidore Schlesinger, a white American immigrant, founded African Mirror, the continent’s first newsreel, in 1913 (Tiendrebeogo and et al. 2021, 215).

At the start of World War II, African Mirror began employing sound, “which accelerated Afrikaner nationalism and saw the establishment of the Reddingsdaadbond Amateur Rolprent Organisasie in 1940 to produce ‘culturally-specific’ Afrikaans films” (Tiendrebeogo and et al. 2021, 215). The industry would be dominated by Afrikaans nationalistic films until the end of Apartheid (Tiendrebeogo and et al. 2021, 215).

The South African National Film Board was created in 1942, and in 1963, the Publications Control Board (Censorship Board) was established (Tiendrebeogo and et al. 2021, 215). Censorship stilfed the industry for some time, as films were banned for various reasons: Zulu (1964), a worldwide success, was “banned at home for screening to Black people,” as was Groen Koering “for portraying an Afrikaans girl who gets pregnant out of wedlock” (Tiendrebeogo and et al. 2021, 215).

Simon Sabela was the first Black South African to produce a local film in 1974, signaling a change in the political climate. In the following decades, many films were produced that were critical of Apartheid, including Road to Mecca (1991) and Place of Weeping (1986) (Tiendrebeogo and et al. 2021, 215). However, cinemas wouldn't screen these films for legal reasons; the most popular local films were instead “slapstick comedies that poke[d] fun at South Africans and local issues” (Tiendrebeogo and et al. 2021, 216).

The end of apartheid in 1994 marked a turning point for South African film. The documentary medium, a popular entry point for emerging filmmakers that saw its golden era in the 1990s, allowed creators to focus “on history and the evolution of a new South African identity and culture” (Tiendrebeogo and et al. 2021, 216).

The industry flexed its prowess during the 2000s with features like the Oscar-winning films Tsotsi (2005) and Yesterday (2004) (Tiendrebeogo and et al. 2021, 216).

Continuing its global reach through its partnership with streaming giant Netflix, the platform recently released a preview of upcoming media, heading the article “A Commitment to Variety and Authenticity With Local Films and Series” (“Netflix Presents a Preview of Its South African Productions and Partnerships at MIP Africa” 2023).

South African media emergence

South African films followed the path of the anti-Apartheid movement. Filmmakers emerged to create media that reflected the complexities of Black South Africans and their struggles.

See sources through link above.

South Africa-U.S. Media relationship

Like Nigeria, South Africa is lumped together with other African countries in terms of portrayal in the U.S. media. However, a significant body of U.S. media is focused on Apartheid and Nelson Mandela, the anti-Apartheid activist and first president of South Africa who has become a global icon due largely to his multiple Hollywood portrayals (Lukhele 2012, 289). Media like Mandela (1987), Mandela and De Klerk (1997), Catch a Fire (2006), Invictus (2009), and more highlight different narratives of the Apartheid era and the life of Mandela.

Mandela is seen similarly to civil rights activist Martin Luther King Jr. From the white gaze, they are both Black people who have “risen above” stereotypes dominant groups have placed on them, making them appealing to white, and global, audiences (so long as their images are sanitized). His portrayal is less beneficial for South Africans and more to the benefit of “the architects of [his portrayal] namely, Wall Street, which is instrumentalizing Mandela to script a jaundiced narrative of South African culture and history” (Lukhele 2012, 289).

Analyzing the context

Ethical

imperative

Before, during, and after the end of Apartheid, South African creators realized the ethical imperative of telling their own stories to combat their colonized image. The documentary medium in particular allowed producers to share South African stories with a global audience. Examples include Steps for the Future (2001) and Generation Africa (2021) (Tiendrebeogo and et al. 2021, 216)

subaltern

flows

Similar to Nigeria, South African creators challenged the one-way flow of media from Western and white South African producers by distributing their own media. However, one challenge lies in the flow and appropriation of Mandela’s image. His media portrayals are a method of containing his more Black radical identity that stands in opposition to U.S. national interests (Lukhele 2012, 290).

Importance of emergence

Soft

power

Overall, Nigerian producers, South African producers, and producers from other African countries were driven by the harmful effects of colonial representation and a desire to generate income to establish their own media cultures. Narratives showcasing the diversity of the Nigerian and South African experiences countered dominant views of Africans as backward, hopeless, and lacking in agency.

By adopting the West’s tools of media hegemony, “communities in Africa are able to intervene directly in the dominant cinema’s discourse. [...] This challenge to western hegemony is both pragmatic and constant. This is how the communities interpolate their own cultural realities” (Mhando 2009, 28). This intervention of dominant cinema gives African countries the soft power to influence how other countries view and shape narratives of the continent. Just as Hollywood has

shaped global media discourse, Nollywood and South African media industries can shape how the U.S., and the world, views their countries and Africa.

As Nigerian and South African media evolved, their stories included more narratives that spoke to common themes experienced by people from different cultures, like Tsotsi and Òlòtūré. Not to say that media steepd in very specific cultural contexts cannot do this, but narratives that speak to universal themes have the soft power to change perceptions over time.

Implication for other countries

Intentions

Modeling

The relationship between U.S. media and Africa is changing, giving other countries new opportunities to establish themselves in U.S. media markets. However, centuries of colonialism have not disappeared with this changing relationship. The U.S.’s priority is still its own interest. Platforming African creators is ultimately to its own benefit, giving media companies the image of diversity and inclusiveness while sharing narratives it deems worth sharing.

South Africa and Nigeria established their media cultures by countering the harmful media of the colonial era. While other countries don’t necessarily have to mine their national trauma in order to cross over into U.S. markets, they can (continue) showcasing their histories and cultures in ways that counter colonial narratives. Creating media with narratives that are universal, like Tsotsi and Òlòtūré, is also a great method of crossing over.

How can U.S. media companies

further work with african producers?

Intentions

partnerships

Believe in the creativity of people within the continent without having to justify it through what the U.S. produces (Black Panther). African producers have been creating and distributing narratives and circulating through film festivals for decades. Establish authentic relationships with creatives by understanding the cultural, social, and historical contexts they are situated in.

U.S. media companies who have not yet formed relationships with African producers can observe what companies are doing, and more importantly, what they can do better that also respects African agency and dignity. They can take the initiative of exploring new relationships without “acting on” to racial injustice and diversifying their content to avoid scrutiny from the public.

References

“About Us – Africa Movie Academy Awards.” n.d. Accessed December 15, 2023. https://ama-awards.com/about-us/.

Akande, Segun. 2017. “The First Movie Ever Made in Nigeria Was Proudly Racist.” Pulse Nigeria. October 6, 2017. https://www.pulse.ng/entertainment/movies/palaver-the-first-movie-ever-made-in-nigeria-was-proudly-racist/r90mvq4.

“Alexandria Why? The Beginnings of the Cinema Industry in Alexandria, AlexCinema.” n.d. Accessed December 10, 2023. https://www.bibalex.org/alexcinema/historical/beginnings.html.

“Black Panther.” n.d. Box Office Mojo. Accessed December 10, 2023. https://www.boxofficemojo.com/title/tt1825683/.

Cham, Mbye B. 2011. “Film and History in Africa: A Critical Survey of Current Trends and Tendencies | African Film Festival, Inc.” African Film Festival New York. Accessed December 9, 2023. https://africanfilmny.org/articles/film-and-history-in-africa-a-critical-survey-of-current-trends-and-tendencies/.

Dargis, Manohla. 2006. “From South Africa, a Tough Thug Shows His Big Heart.” The New York Times, February 24, 2006, sec. Arts. https://www.nytimes.com/2006/02/24/movies/from-south-africa-a-tough-thug-shows-his-big-heart.html.

Davis, Peter. 2009. “In Africa, Diamonds Are Forever: From <em>The Great Kimberley Diamond Robbery to Blood Diamond</Em>.” August 18, 2009. https://www.screeningthepast.com/issue-25-special-issue-colonial-africa-on-the-silent-screen-recovering-the-rose-of-rhodesia-1918/in-africa-diamonds-are-forever-from%c2%a0the-great-kimberley-diamond-robbery%c2%a0to%c2%a0blood-diamond/#lightbox[6755]/0/.

Dellatto, Marisa. 2023. “The World’s Largest Media Companies In 2023: Comcast And Disney Stay On Top.” Forbes. Accessed December 5, 2023. https://www.forbes.com/sites/marisadellatto/2023/06/08/the-worlds-largest-media-companies-in-2023-comcast-and-disney-stay-on-top/.

Gathara, Patrick. 2021. “Opinion | ‘Black Panther’ Offers a Regressive, Neocolonial Vision of Africa.” Washington Post, October 28, 2021. https://www.washingtonpost.com/news/global-opinions/wp/2018/02/26/black-panther-offers-a-regressive-neocolonial-vision-of-africa/.

Hayward, Susan. 2005. Cinema Studies: The Key Concepts. 2. ed., Repr. Routledge Key Guides. London: Routledge.

Jordache A. Ellapen. 2016. “Reviewed Work: South Africa’s Renegade Reels: The Making and Public Lives of Black-Centered Films by Litheko Modisane.” Black Camera 8, no. 1: 250. https://doi.org/10.2979/blackcamera.8.1.0250.

Kavoori, Anandam P. 2009. The Logics of Globalization: Studies in International Communication. Lanham, MD: Lexington Books.

Kemp, Grethe. 2019. “A Silverton Siege Movie Is Coming.” City Press. March 31, 2019. https://www.news24.com/citypress/trending/a-silverton-siege-movie-is-coming-20190330.

Krumrey, Karen. 2022. “Chapter 1 – The Study of Intercultural Communication,” September (September). https://openoregon.pressbooks.pub/comm115/chapter/chapter-1-2/.

Leaman, O. 2003. Companion Encyclopedia of Middle Eastern and North African Film. Taylor & Francis. https://books.google.com/books?id=LmSFAgAAQBAJ.

Lukhele, Francis. 2012. “Post-Prison Nelson Mandela: A ‘Made-in-America Hero.’” Canadian Journal of African Studies / Revue Canadienne Des Études Africaines 46, no. 2 (August): 289–301. https://doi.org/10.1080/00083968.2012.702088.

Mhando, Martin. 2009. “Globalization and African Cinema: Distribution and Reception in the Anglophone Region.” Journal of African Cinemas 1, no. 1 (July): 19–34. https://doi.org/10.1386/jac.1.1.19/1.

Moemeke, Rita, Emen Akpabio, and Patrick Enaholo. n.d. “Kongi’s Harvest: From Stage to Screen.” Google Arts & Culture. Accessed December 11, 2023. https://artsandculture.google.com/story/kongi-s-harvest-from-stage-to-screen/mwXxBLUHWBJUIQ.

Moses, Ben, Marcel Ikeji, and Victor Jorshe. 2021. “Portrayal of Nigeria in Hollywood TV Series: A Content Analysis of ‘Black-Ish’ and ‘Bob Hearts Abishola.’” https://www.academia.edu/47734674/Portrayal_of_Nigeria_in_Hollywood_TV_Series_A_Content_Analysis_of_Black_ish_and_Bob_Hearts_Abishola_.

Neophytou, Nadia. 2018. “In Cannes, African Filmmakers Are Plotting to Take Back Control from European Producers.” Quartz. May 19, 2018. https://qz.com/africa/1282690/african-filmmakers-in-cannes-2018-want-to-take-back-control-from-european-producers.

Nakayama, Thomas K., and Rona Tamiko Halualani, eds. 2010. The Handbook of Critical Intercultural Communication. Handbooks in Communication and Media. Chichester, West Sussex, U.K. ; Malden, MA: Wiley-Blackwell.

“Netflix Presents a Preview of Its South African Productions and Partnerships at MIP Africa.” 2023. About Netflix. September 4, 2023. https://about.netflix.com/en/news/netflix-presents-a-preview-of-its-south-african-productions-and-partnerships.

“Nigeria.” 2023. In The World Factbook. Central Intelligence Agency. https://www.cia.gov/the-world-factbook/countries/nigeria/.

Nwajiaku, Vivian Nneka. 2022. “‘Silverton Siege’ Review: Is This Film about the Silverton Trio? Not Really - Afrocritik.” April 29, 2022. https://www.afrocritik.com/silverton-siege-review-is-this-film-about-the/.

Nye, Joseph S. 1990. “Soft Power.” Foreign Policy, no. 80: 153. https://doi.org/10.2307/1148580.

Okonjo, Jide. n.d. “10 Best Nigerian Characters in Hollywood.” Geeks. Accessed December 13, 2023. https://vocal.media/geeks/10-best-nigerian-characters-in-hollywood.

Roxborough, Scott. 2022. “Netflix Unveils 2022-2023 African Originals Slate.” The Hollywood Reporter (blog). August 2, 2022. https://www.hollywoodreporter.com/tv/tv-news/netflix-2022-2023-african-movies-shows-1235190889/.

Salaudeen, Aisha. 2020. “New Nollywood Film Shines a Light on Human Trafficking in Nigeria.” CNN. October 7, 2020. https://www.cnn.com/2020/10/07/africa/human-trafficking-film-nigeria/index.html.

Thackway, Melissa. 2003. Africa Shoots Back: Alternative Perspectives in Sub-Saharan Francophone African Film. Bloomington: Indiana University Press.

Thussu, Daya Kishan. 2018. International Communication: Continuity and Change. Third edition. London ; New York: Bloomsbury Academic.

Tiendrebeogo, Toussaint, et al. 2021. “The African Film Industry.” Unesco. Accessed October 28, 2023. https://unesdoc.unesco.org/ark:/48223/pf0000379165/PDF/379165eng.pdf.multi.

Top Streaming Services by Subscribers • FlixPatrol.” n.d. FlixPatrol. Accessed December 8, 2023. https://flixpatrol.com/streaming-services/subscribers/.

Truitt, Brian. 2018. “Daring, Diverse ‘Black Panther’ Promises to Be ‘Cultural Touchstone.’” USA Today. January 29, 2018. https://www.usatoday.com/story/life/movies/2018/01/29/marvel-black-panther-superhero-diversity-cultural-touchstone-event/1071858001/.

Walsh, Declan, and Hannah Reyes Morales. 2023. “The World Is Becoming More African.” The New York Times, October 28, 2023, sec. World. https://www.nytimes.com/interactive/2023/10/28/world/africa/africa-youth-population.html.

“In looking at filmmaking, in particular, and the other creative arts, in general, one is looking at particular insights into ways of thinking and acting on individual as well as collective realities, experiences, challenges and desires over time” (Cham 2011).

Mariama Dumbuya

American University, School for International Service

Intercultural and International Communication Graduate Student

md5456a@american.edu

SIS 640: International Communication - Final Project

December 15, 2023

You think your pain and your heartbreak are unprecedented in the history of the world, but then you read.

James Baldwin